Muonic atoms

Muonic atoms are exotic systems in which one electron is replaced by a muon, it’s heavier cousin (200 x heavier than an electron) and a short-lived elementary particle. This substitution drastically alters the atom’s properties, providing researchers with a powerful tool to probe the fundamental forces of nature and the structure of atomic nuclei with unprecedented precision. Through the study of muonic atoms, we gain valuable insights into quantum electrodynamics, nuclear physics, and the underlying principles governing the universe.

The LKB team works on two majors projects related to muonic atoms:

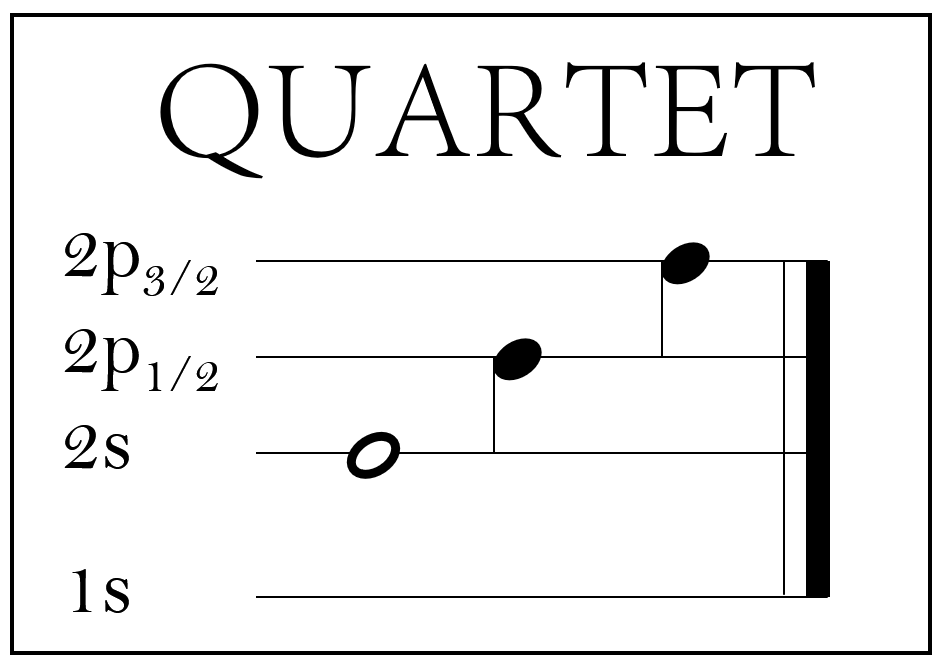

- QUARTET is a collaboration that uses magnetic microcalorimeter detectors (MMCs) developed at KIP in Heidelberg and muonic atom spectroscopy at the Paul Scherrer Institute to improve the charge radii of light nuclei.

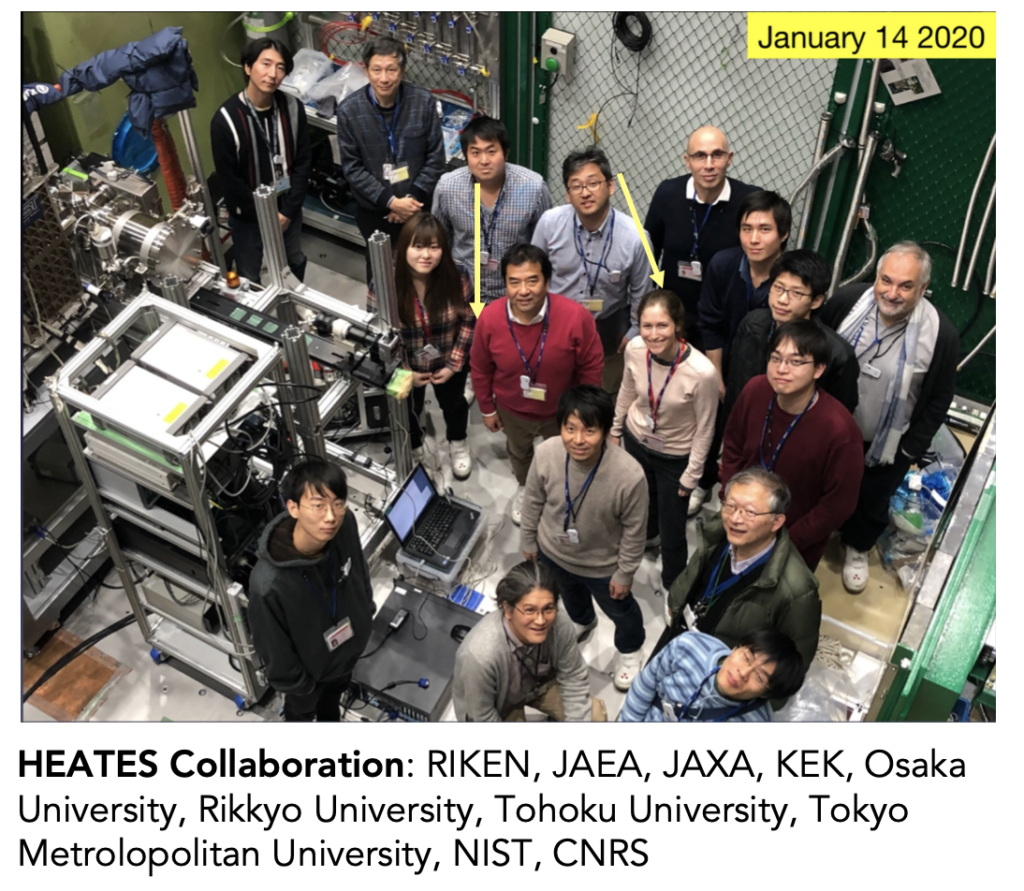

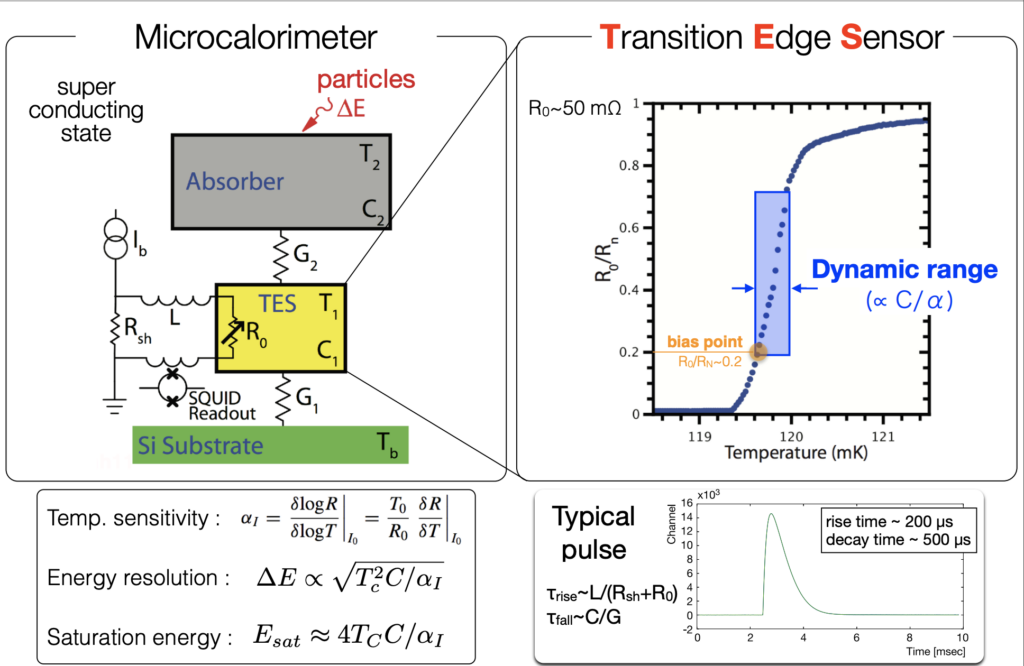

- HEATES is a collaboration led by colleagues from RIKEN in Japan that uses transition edge sensor (TES) microcalorimeter detectors to perform spectroscopy of Rydberg states for strong-field QED tests.

QUARTET

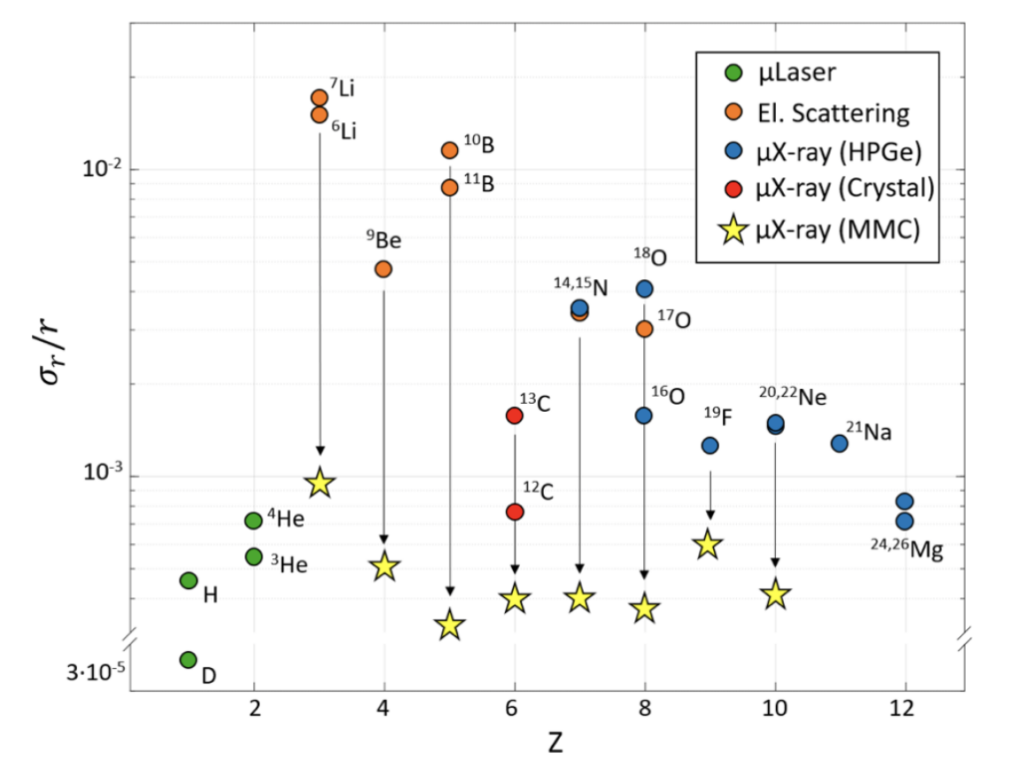

Current status and opportunities with improved radii of light nuclei. The vertical axis is the fractional uncertainty, with the data-points corresponding to the current most precise values for each nucleus. The values include nuclear theory uncertainties. The stars denote the accuracy goals which can be reached within the QUARTET project considering both experimental and theoretical uncertainties.

Muonic atoms are exotic bound systems consisting of a negative muon, a nucleus, and possibly several electrons. Due to the heavy mass of the muon (mμ ∼ 200me), it’s Bohr radius is much smaller than in electronic atoms and thus for low angular momentum states the muon has a large overlap with the nuclear wavefunction. The nuclear properties lead to measurable shifts in the atomic transition energies, making muonic atom spectroscopy an effective probe of phenomena such as nuclear finite size effects, relativistic QED contributions, and short-range interactions carried by new heavy mediators. These systems are particularly well suited to accurately determine RMS nuclear charge radii, which can be obtained via the spectroscopy of the low-lying radiative transitions (mostly 2P − 1S) in muonic atoms.

With the exception of 12C, radii in the range Z = 3 − 10 are the least well-measured in the stable region of the nuclear chart. This has several causes: The first is that the fractional contribution of the finite nuclear size to the binding energy of hydrogenic systems scales as Z2, so that a high absolute accuracy is needed when considering light elements. However, the relevant transitions lie below a few hundred keV, making x-ray spectroscopy using solid-state detectors highly limited by the intrinsic resolution of these detectors, which is typically several hundred eV. Laser spectroscopy of muonic atoms can reach an excellent accuracy, however it has only been applied to Z = 1, 2, and is challenging to extend to higher Z . This is due to the wide search region stemming from the current uncertainty in the radii, and in the difficulty in making high- power lasers. Finally, x-ray spectroscopy using crystal spectrometers offers high resolution in the keV regime (up to ∼ ppm). Unfortunately, it suffers from low efficiency and a narrow bandwidth, making crystal spectroscopy impractical to extend to the entire series of light elements.

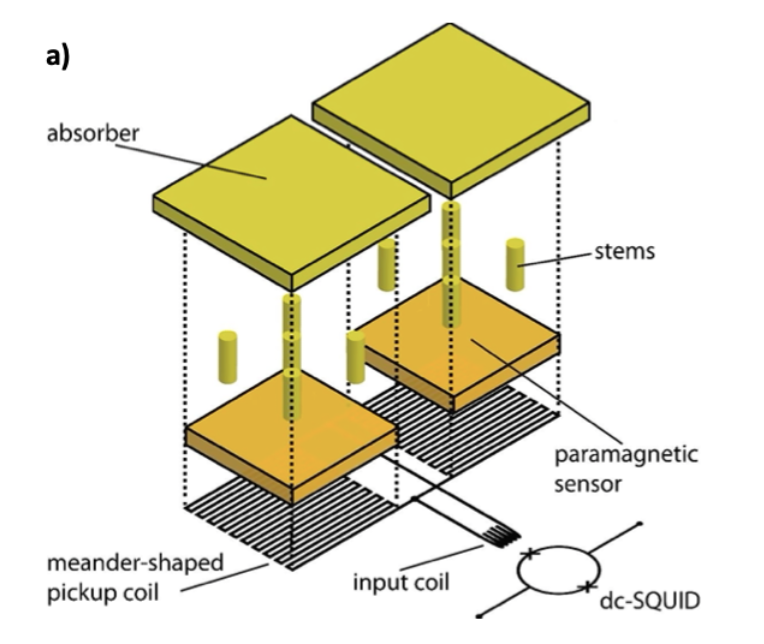

The QUARTET collaboration will measure the radii of light nuclei (3 ≤ Z ≤ 10) with up to an order of magnitude higher accuracy than their current experimental values. To do this we will carry out high resolution muonic x-ray spectroscopy utilizing quantum sensing detectors: metallic magnetic calorimeters (MMCs). These detectors combine the highest resolving power with broadband capabilities in the energy range of interest, while remaining an order-of-magnitude more efficient than crystal spectrometers. These are novel low temperature detectors characterized by an excellent energy resolution, fast response time and a good linearity. MMCs can be described as composed of an absorber, whose dimensions are optimized for the particles or photons to be detected, which is thermally connected to a paramagnetic temperature sensor sitting in a constant magnetic field. The sensor is weakly coupled to a thermal bath kept at a constant temperature, typically below 30 mK. An incident photon induces an increase in temperature of the absorber, which leads to a decrease of the magnetization of the paramagnetic sensor which is detected as a change of magnetic flux in a suitable superconducting pick-up coil. This, in turn, is coupled to a low-noise, high-bandwidth DC-SQUID, as front-end of the two-stage SQUID readout. The working principle of MMCs is based on near equilibrium thermodynamics, which is well understood. Therefore the detector response of MMCs can be precisely modeled, allowing for detector design optimization and reliable metrology.

The QUARTET experimental program (2023-2027)

The first successful QUARTET test beam was conducted in October 2023 as described and focused on the transitions in muonic Li, Be, and B. In 2024 QUARTET became an official PSI experiment and will begin its multi-year physics program focusing on x-ray transition energies up to ~80 keV, which can be measured with the maX-30 detector as employed for the test beam. This includes Li, B, B, and C isotopes, and the physics campaigns will be performed with a new, optimized maX-30 detector optimized for QUARTET. These measurements should be made in 2024 and 2025, with approximately 2-3 weeks of beam time each year. Then, a second stage of measurements will be performed in 2026-2027 focusing on the higher energy transitions including muonic N, O, F, and Ne. These transitions require a different detector, the maX-100, optimized for the 100 keV regime.

To learn more about QUARTET, check out

- Towards Precision Muonic X-ray Measurements of Charge Radii of Light Nuclei, B. Ohayon et al, Physics 6, 206-215 (2024).

- MMC Array to Study X-Ray Transitions in Muonic Atoms, D. Unger et al, J Low Temp Phys 216, 344–351 (2024)

HEATES

The small Bohr radius of muonic atoms means that their atomic bound states are found in strong Coulomb fields. In fact, not just the lowest-n states, but an ensemble of states are in this strong-fields. A regime of transitions can be identified between circular Rydberg states in muonic atoms where second-order QED effects are larger than the contributions from nuclear effects. The HEATES collaboration aims at performing high-precision spectroscopy of these states for probing strong-field QED, and notably the vacuum polarization effect which is dominant in exotic atoms.

The HEATES measurements are performed at the J-PARC facility located in Tokai, Japan using a pulsed muon beam and the D2 beamline at the Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility (MLF) at J-PARC. MLF provides the necessary intense pulsed negative muon beams with energies down to 58 keV (3.5 MeV/c). This enables us to stop isolated muons directly at high rates in low-density gas targets. The JPARC scientific committee accepted the HEATES program for the period of 2020-2025, with the goal of performing a sequence of QED tests on gaseous targets : Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe.

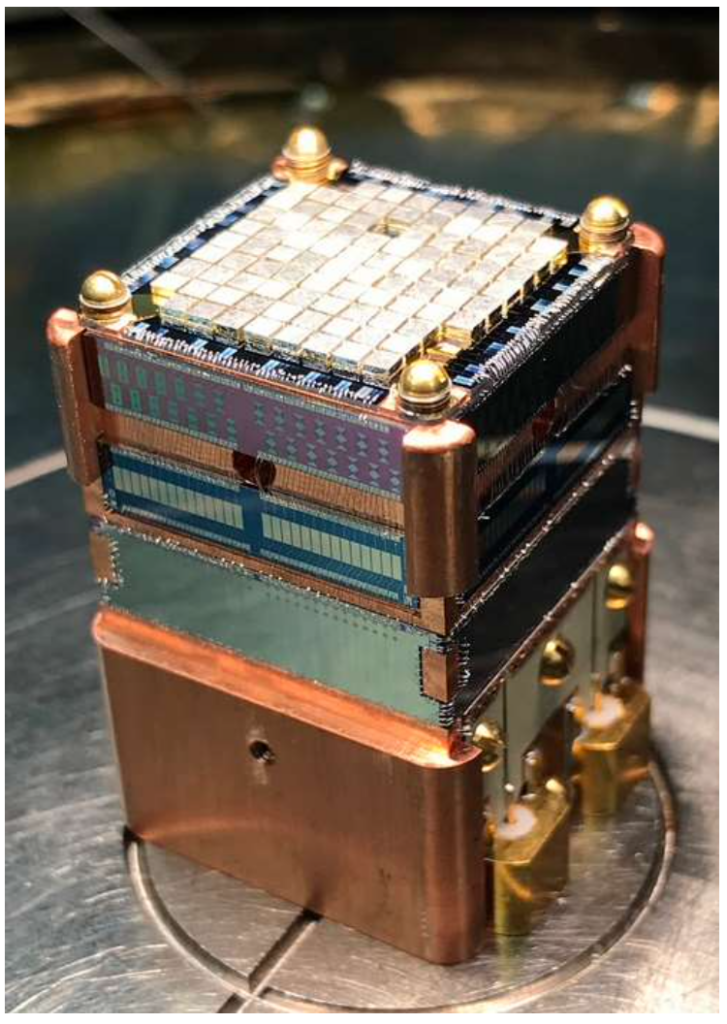

The key to the HEATES program are the hard x ray TES detectors developed by the Quantum Sensing Division at NIST in Boulder, Colorado. The HEATES x-ray detector is based on a 240-pixel TES array, cooled with a pulse-tube-backed adiabatic demagnetization refrigerator (ADR). Each pixel contains a TES consisting of a bilayer of thin Mo/Cu films whose superconducting critical temperature is about 107 mK, and a 4 μm-thick Bi absorber for converting an x-ray energy into heat. The TES can detect x rays up to 10 keV, and the absorption efficiency of the Bi layer is 85% at 6 keV. The effective area of each pixel is 305 × 290 μm2 and the total active area of the array is about 23 mm2. This detector was deployed for campaigns in 2019-2022, and a new, higher energy TES with Sn absorbers was added starting in 2023.

The first measurements of muonic Ne were successful and demonstrated the long-term feasibility of the scientific program, while highlighting the key systematic effects. The high intrinsic resolution of the detector also revealed unexpected signatures of the muonic atoms cascade, which opened a whole new domain of studies of exotic atom dynamics, never visible before.

To learn more about the HEATES physics program, check out:

- Testing Quantum Electrodynamics with Exotic Atoms, N. Paul et al, Physical Review Letters 126, 173001 (2021).

- Deexcitation Dynamics of Muonic Atoms Revealed by High-Precision Spectroscopy of Electronic 𝐾 X Rays, T. Okumura et al, Physical Review Letters 127, 053001 (2021).

- Proof-of-Principle Experiment for Testing Strong-Field Quantum Electrodynamics with Exotic Atoms: High Precision X-Ray Spectroscopy of Muonic Neon, T. Okumura et al, Physical Review Letters 130, 173001 (2024).